What makes a movie unforgettable? I started thinking about that recently after watching an engrossing six-hour film over three consecutive evenings. The Best of Youth (La Meglio Gioventù)  directed by Marco Tullio Giordana originally aired in 2003 as a miniseries on Italian television. It is a family saga centered on two brothers, Nicola and Matteo Carati, who are very different but who want to change the world for good.

directed by Marco Tullio Giordana originally aired in 2003 as a miniseries on Italian television. It is a family saga centered on two brothers, Nicola and Matteo Carati, who are very different but who want to change the world for good.

Spanning four decades, the lives of these two men are punctuated by several major events in Italian history beginning with the flooding of the Arno River in Florence in 1966. It is a time of emerging social consciousness in the youth of both Europe and America. Young people from many countries have come to Florence to help salvage ancient books and manuscripts—“mud angels” they were called. Nicola and Matteo are there with two school friends and are about to start on a male-bonding road trip to celebrate the end of exams. It is here that their lives diverge.

I found this film compelling throughout the six hours; if I had to rank it, I would give it four stars out of five. Why? First of all, it has the essentials: it depicts the human condition with good acting, a compelling story, and fully realized characters. For me, a film must look and feel like truth. The actors must portray characters who look and act and speak like real people. Writing real dialogue must be hard because it is rare. I later learned that the two writers on Youth were a man and woman who often work together. Maybe that’s the key, both genders and a certain familiarity/simpatico with each other’s working style.

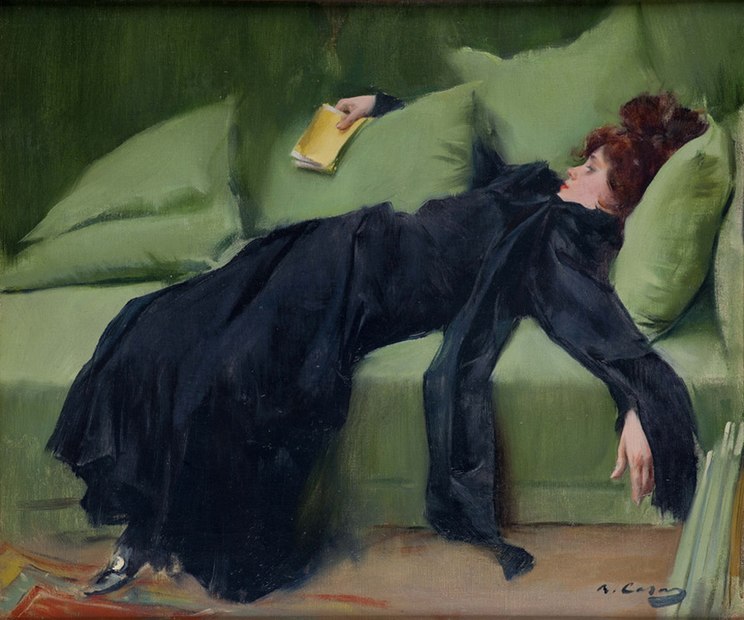

What else? Well, I like a film that slows down the emotion, gives the viewer time to think and, thereby, participate in it. If you feel it, you’ll likely remember it. I have dozed off in films with gratuitous sex or violence because it isn’t real, it isn’t happening ‘to me’…it’s often not even happening to the character but to the caricature actor who cannot NOT be him- or herself…it’s happening to Angelina or Tom or Russell or Nicholas. But I cried several times throughout Youth. Giordana understands that the small events in life often become turning points. He lets the camera linger on nuances—the face, the hands, the eyes. Matteo’s advice to Mirella on how to capture mystery in her photographs—”to find the soul you have to look inside”—is no doubt Giordana’s theory of how to capture mystery with a movie camera.

I like the silences in this film. For me, nothing is as powerful as the body’s stillness in intimate moments. And if authentic dialogue is difficult for a writer, silence must be even more so because it so antithetic to the ego. Silence, what isn’t said, makes the viewer work harder—you are forced to read the character’s mind, to make an interpretation, instead of simply being told what he or she is thinking. And science backs up my theory that silence helps embed scenes and thereby increases a film’s chance of being memorable. It’s almost like a mnemonic aid; in neurological terms, it’s called depth of processing—the amount of effort and cognitive capacity employed to process information—the greater the effort, the deeper it sticks. It also applies to fiction writing—that old admonition by the world’s great writers: show, don’t tell.

Youth also has other things I love: literature, music, photography—a sort of sweet homage to the arts—and, of course, bella Italia  . There are cemeteries (please, don’t leave out death, the most universal act), an amazing library in Rome, and books throughout. My favorite line is about books, delivered by Mirella to Matteo, frustrated by his remoteness, his inability to show or accept love: “The reason you like books so much is because you can close them whenever you want. Life isn’t like that. You don’t decide.” Wham.

. There are cemeteries (please, don’t leave out death, the most universal act), an amazing library in Rome, and books throughout. My favorite line is about books, delivered by Mirella to Matteo, frustrated by his remoteness, his inability to show or accept love: “The reason you like books so much is because you can close them whenever you want. Life isn’t like that. You don’t decide.” Wham.

So, there it is in three words…”you don’t decide.” A great film honors a core truth about human experience–in this case, that predominate truth seems to be that life refuses to be planned; it drifts and lurches without, and despite, maps or direction. Movie heroes (usually played by caricature actors) are never at the mercy of fate (or biology, or time), they get to decide—the plot and dialogue are artificially manipulated to let them decide—but it rings false every time. Real heroism is not about decisions but how one reacts in the aftermath of making difficult choices. See this film. You’ll remember it.

You’ve inspired me to add this film to my list! Fascinating idea on silence, Judy. I’ve always been impressed by playwrights such as Pinter, and Beckett (and of course Tarantino, who was influenced by Pinter) who used silences and pauses in their plays. Silences are uncomfortable for the audience, who shuffle and clear their thoughts and maybe that’s because, as you say, the viewer has to work harder, to interpret the character. We don’t like to have to work at interpreting characters because maybe we face up to our own characters—and we don’t like what we see. Note the last two sentences of this quotation from Pinter:

There are two silences. One when no word is spoken. The other when perhaps a torrent of language is being employed. This speech is speaking of a language locked beneath it. That is its continual reference. The speech we hear is an indication of that which we don’t hear. It is a necessary avoidance, a violent, sly, anguished or mocking smoke screen which keeps the other in its place. When true silence falls we are still left with echo but are nearer nakedness. One way of looking at speech is to say that it is a constant stratagem to cover nakedness. We have heard many times that tired, grimy phrase: ‘failure of communication’ … and this phrase has been fixed to my work quite consistently. I believe the contrary. I think that we communicate only too well, in our silence, in what is unsaid, and that what takes place is a continual evasion, desperate rearguard attempts to keep ourselves to ourselves. Communication is too alarming. To enter into someone else’s life is too frightening. To disclose to others the poverty within us is too fearsome a possibility.